1.1.4 Concepts of the scanning law

Author(s): Jos de Bruijne

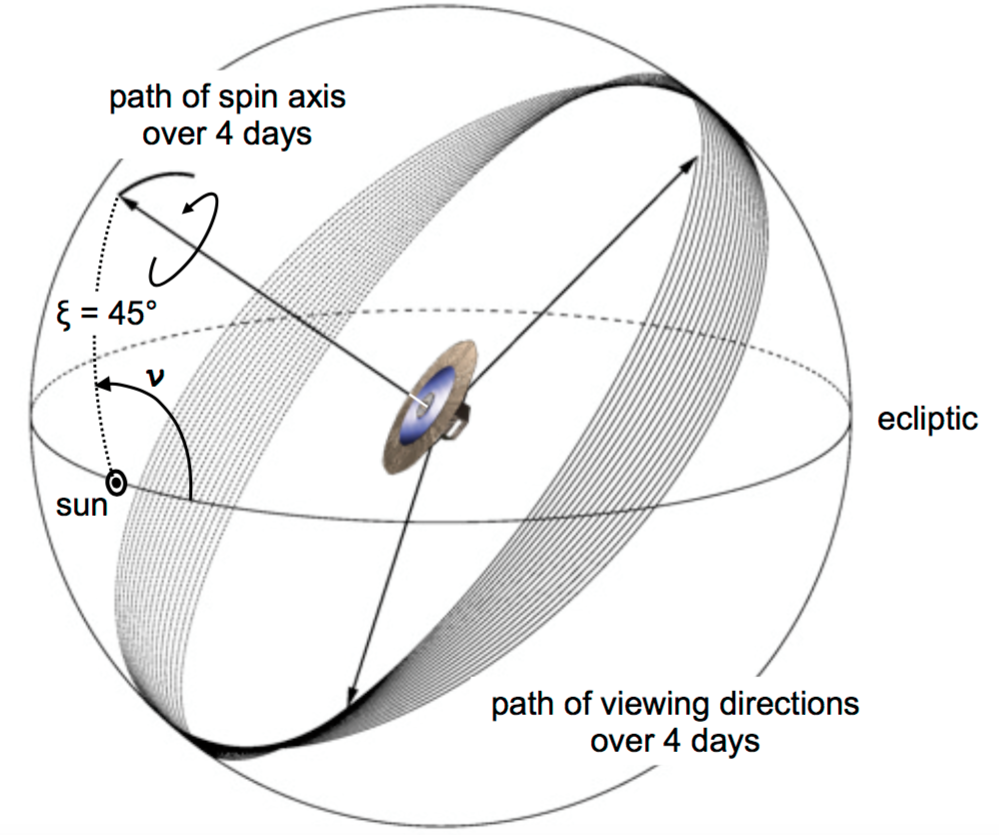

The scanning law of Gaia determines how the spacecraft scans the sky. It is explained in Gaia Collaboration et al. (2016b) and shown schematically in Figure 1.8. The scanning motion consists of three, effectively independent components: a six-hour rotation around the spin axis (at a nominal spin rate of arcsec s), a 63-day precession (at a fixed Solar-aspect angle of ) of the spin axis around the Solar direction, and the annual motion of the Earth/L2 with respect to the Sun. This combination of motions enables full-sky coverage in at least two different scan directions every six months and, on average, about 70 (astrometric and photometric) focal-plane transits over the nominal, five-year mission for each source (Table 1.5). The scanning law is illustrated in this video. As described in Section 1.3.2, two scanning laws (EPSL and NSL, described in Section 1.1.4 and Section 1.1.4, respectively) have been employed in the time range applicable to Gaia DR3 (25 July 2014 to 28 May 2017).

The slow but continuous precession causes a small across-scan motion of all object images during their passage of the focal plane. The size of this motion varies with time over the six-hour spin period and is described by a sinusoid (with a period of six hours) with an amplitude of 173 mas s, which is roughly one across-scan pixel per second. The sinusoids of the two fields of view are phase-shifted by the basic angle multiplied with the spin rate, i.e., by 106.5 minutes of time. Across-scan motion causes two, time-variable effects: (i) an across-scan shift of all images during a CCD transit, which is corrected for in the on-board window-propagation software, and (ii) an across-scan smearing of the PSF during a CCD transit, which is calibrated in the ground processing.

Ecliptic-poles scanning law

During the first month of the nominal mission, a special, ecliptic-poles scanning law (EPSL) has been adopted (see also Section 1.3.2 and Gaia Collaboration et al. 2016b) with as main goal to bootstrap various calibrations needed in the ground-processing software (e.g., focal-plane geometry and PSF). The EPSL is particularly useful in this respect since there is no precession of the spin axis around the Solar direction and hence no across-scan motion and PSF smearing: the spin axis only follows the motion of the Sun along the ecliptic plane to maintain a constant Solar-aspect angle of . In addition, with the EPSL, the field-of-view directions scan the northern and southern ecliptic poles on each six-hour spin, giving an extremely frequent sampling of these regions.

Nominal scanning law

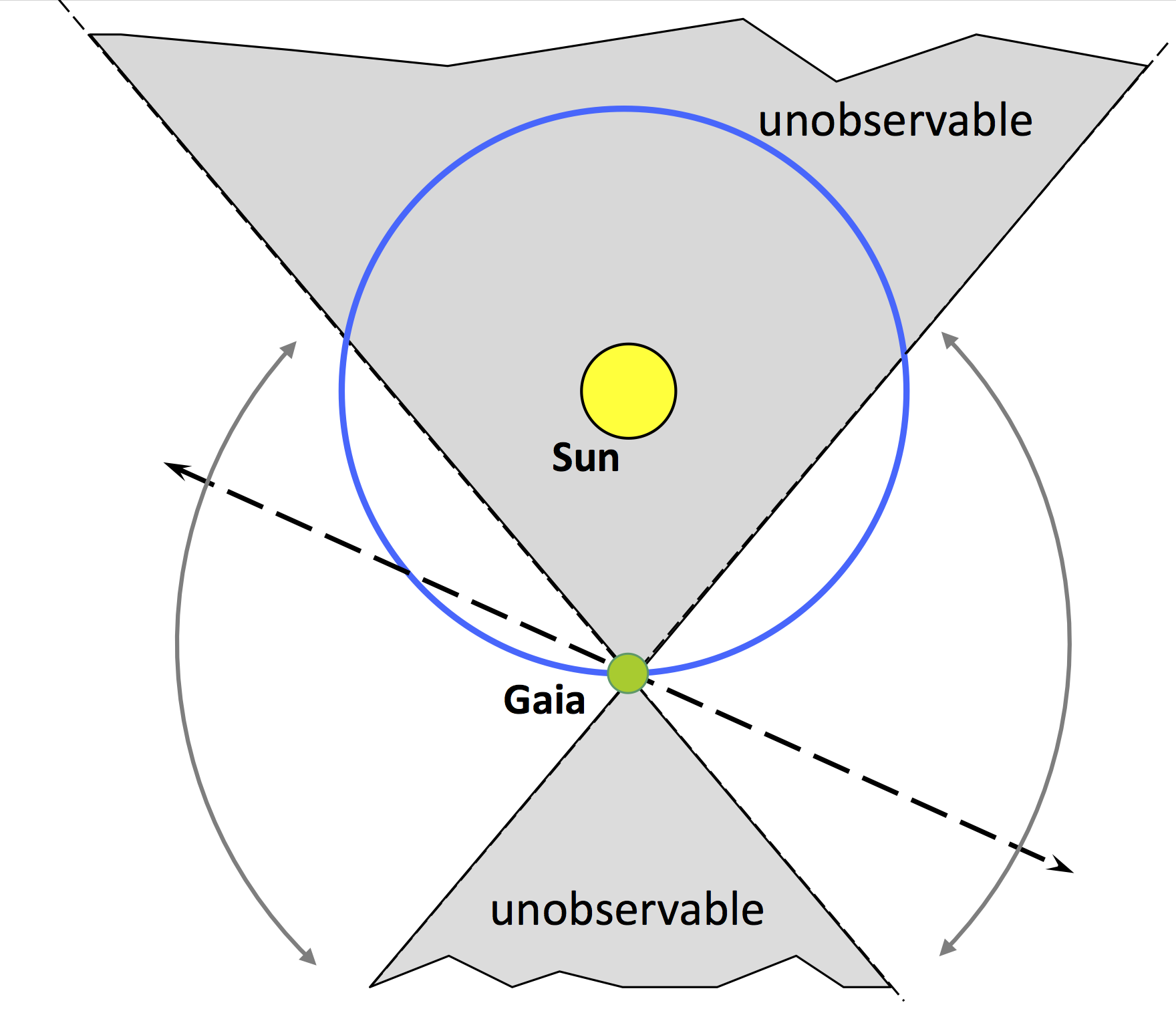

During the remainder of the mission, the nominal scanning law (NSL) has been used (see also Section 1.3.2 and Gaia Collaboration et al. 2016b). In the nominal scanning law, Gaia’s spin axis precesses, with a period of 63 days, on a cone around the Solar direction with an opening angle (the so-called Solar-aspect angle) of . As a result, the scanning plane (‘great circle’) varies its inclination with respect to the ecliptic between 90and 45, such that its nodal direction can only have a Solar elongation between 45and 135. By considering the intersection of the scan plane with the ecliptic, as shown in Figure 1.9, it becomes immediately clear that Solar-system asteroids are never observed by Gaia at less than 45elongation, both from the Sun and from the anti-Solar direction (opposition). This specific geometry of observation has important consequences for Solar-system-object observations. In particular, main-belt asteroids are not only always observed at non-negligible phase angles but also in a variety of configurations (i.e., high/low proper motion, small/large distance, etc.) such that the detection capabilities of Gaia and the accuracy of its measurements vary, for a given asteroid, from observation to observation.

During the nominal five-year mission, the scanning law results in an average of 70 usable astrometric and photometric and 40 usable spectroscopic focal-plane transits for a given star (with a further 70 astrometric and photometric and 40 spectroscopic transits expected for a five-year extended mission). As a result of the scanning law, there is a significant variation of the number of end-of-mission transits as function of position on the sky, in particular as function of ecliptic latitude with regions around being observed more often and regions around the ecliptic poles and plane being observed less frequently (Table 1.5). The number 70 assumes that 20% of the transits collected on board do not produce useful information, for instance as a result of on-board data deletion (Section 1.1.3 and Section 1.3.3). In practice, this is a conservative estimate, in particular for bright stars (Table 1.12).

| [] | [] | ||

| 0.025 | 10.0 | 12.9 | 161 |

| 0.075 | 12.9 | 15.7 | 161 |

| 0.125 | 15.7 | 18.6 | 162 |

| 0.175 | 18.6 | 11.5 | 162 |

| 0.225 | 11.5 | 14.5 | 163 |

| 0.275 | 14.5 | 17.5 | 165 |

| 0.325 | 17.5 | 20.5 | 166 |

| 0.375 | 20.5 | 23.6 | 168 |

| 0.425 | 23.6 | 26.7 | 171 |

| 0.475 | 26.7 | 30.0 | 175 |

| 0.525 | 30.0 | 33.4 | 180 |

| 0.575 | 33.4 | 36.9 | 187 |

| 0.625 | 36.9 | 40.5 | 198 |

| 0.675 | 40.5 | 44.4 | 122 |

| 0.725 | 44.4 | 48.6 | 144 |

| 0.775 | 48.6 | 53.1 | 106 |

| 0.825 | 53.1 | 58.2 | 193 |

| 0.875 | 58.2 | 64.2 | 185 |

| 0.925 | 64.2 | 71.8 | 180 |

| 0.975 | 71.8 | 90.0 | 175 |